princess nike opalemo

In adulthood, sickle cell turned a benign face upon the same individual it pummeled so hard in the early years. Princess Nike Opalemo experiences less frequent and much less severe crises these days. Physically too, things have turned around so well that you would never be able to tell that she has sickle cell anaemia except she tells you herself – a far cry from days of yore when schoolmates regularly taunted her for her fragile looks.

In primary and secondary school, Nike kept to herself – rather, her mates ensured she kept to herself. Because she was usually that pale, they nicknamed her ‘Pale-Face’ – and because she seemed so weak, so fragile, they exempted her – banished her, really – from their activities.

‘We don’t need your type to engage in this with us,’ they would admonish her whenever she attempted to join their girlish doings, ‘you would melt in the attempt!’

Nike was constantly reminded that she was not one of them, not one of the inner circle. Sure, the sickle cell made her to look – and feel – very weak, yet her schoolmates made it worse by branding her with a stamp of uselessness!

Not many of Nike’s schoolmates would ever forget the suddenness with which their colleague descends into sickle cell crises. On many occasions, sometimes in the middle of a lesson, sudden and severe pain crises would drag her right from classroom to hospital bed. Quite an eyeful she gave her mates of the unpredictability of the illness called sickle cell anaemia.

Nike studied Sociology at the Olabisi Onabanjo University (OOU) in Nigeria. Here, as in secondary school, she lived in her own shell. Although she had never been ashamed to tell people she was living the sickle cell challenge, the looks people gave her when they knew – and the things they said afterwards – made her to steel herself against the outside world.

Oversight

After graduation, Nike proceeded to London, where she studied Healthcare and Nursing.

Something in relationships that would lead to parenthood (if not marriage) often prevents many couples from ascertaining their genotype before settling down. It was not until after the birth of her first child that Nike knew her husband’s genotype – AA.

Nike is quick to accept that as an oversight – what if, by mischance, her man was a carrier of the gene combined in her? For a nurse who had seen lots of children and adults in sickle cell pain – and who herself was with sickle cell; and for a nurse who was determined to whittle down the incidence of SCD by carefully choosing her spouse, it was indeed an oversight. An unforgiveable oversight, she would ever admit.

‘Had my husband been anything but (AA),’ she asserts, ‘I would have stopped having children after the first one.’

Nike Opalemo Sickle Cell Foundation (NOSCF)

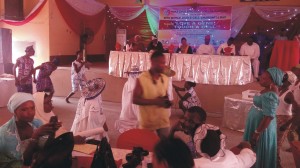

princess nike opalemo scd programme

To add her own quota to sickle cell awareness in Nigeria, Nike founded her own Sickle Cell Foundation in 2009. NOSCF conducts blood donation campaigns and also gives moral and material support to individuals and families facing the sickle challenge.

’I wish I could wave a wand and take away the pain and anxieties of everyone living with SS,’ she says.

To Nike Opalemo, it is forgivable if a couple were ignorant of their genotype and gave birth to a child or children with sickle cell.

‘To know one’s genotype and its implications for a child,’ she says, ‘and still go ahead, for love or passion, to produce a child with sickle cell, is the height of cruelty.’

Nike is critical of couples who, under the catch phrase of ‘informed choice’ go ahead with marriage to give birth to offspring with sickle cell.

‘These couples often declare they are prepared to raise and cater for a child with sickle cell; yet they have not thought out whether the child they are bringing into the world is prepared to live with the disorder.’ In Nike’s opinion, the equation is grossly unfair.

Blood, Blood, Blood

princess nike opalemo sickle cell foundation events

Nike Opalemo strongly believes in giving back to society. Unfortunately, in matters to do with blood, she can only take but not give!

Of the many rounds of blood transfusion Nike had undergone, one episode remains etched in her memory…

Blood Now – Or Never

About 25 years ago, Princess Nike Opalemo lay on a hospital bed in Lagos, waiting for a desperately-needed blood transfusion. Her mother had gone in search of blood; her father was at work. The doctors said the patient must have blood within one hour, otherwise she would die.

Although on bed, Nike was feeling very, very tired. She had overheard the one-hour ultimatum the doctors had given and she kept glancing at the wall clock opposite her bed: would her mother emerge at the door with blood – or was this going to be the End of the Road?

Nike’s concentration was poor but she remembers that five minutes before the psychological moment, her mother had not arrived. As she fell involuntarily into a deep sleep that was more like a coma, she thought perhaps it was the End of the Road.

Consciousness Regained

‘I regained consciousness,’ Nike recalls, ‘to find blood dripping into my veins.’

Her father it was who saved the day. His wife had called him in to assist with the hunt for blood after failing to procure the substance on her own. She had warned: Get your daughter blood within 20 minutes or …

He had hurried from the office barefooted, made enquiries from a passer-by and was directed to a nearby blood bank. The passer-by had been quite frightened less by the urgency of the enquiry as by the manner of the enquirer.

‘I received the much-needed substance – and lived to tell my story.’ Nike says.

She would receive blood again and again in the UK and in Nigeria, but none so dramatic as the one just related.

‘Without blood – without public-spirited blood donors – I wouldn’t be as healthy as I am today.’